Lost in the Haze: The Sense-Making Crisis

- Martin Enlund

- 11/19/24

Imagine a world where the very foundations of knowledge are in question. Where experts disagree on the most basic facts, and the public is left to navigate a sea of conflicting information. Welcome to our reality, where the process of knowledge creation has become unhinged. We’re facing numerous major challenges, from pandemics to climate threats, migration flows, and rapid technological development, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI). But beneath these surface-level issues lies a more profound problem: the mechanisms by which we produce, disseminate, and consume information have been severely disrupted, leading to a crisis of trust in the very foundations of knowledge itself.

Consider the recent pandemic. One epidemiologist predicted hundreds of thousands of deaths, advocating for an immediate and aggressive shutdown of society to mitigate this. Meanwhile, another expert argued that the outbreak is likely no worse than a typical flu season.

Note: this essay is also available in Swedish

The situation is further complicated by the fact that even experts can’t agree on the basics. A prominent infectious disease expert initially claimed that face masks were ineffective during the latest pandemic, only to later admit that they did work, but he had intentionally misled the public to ensure a steady supply for healthcare personnel due to concerns over PPE shortages. The WHO’s expert panel has stated that there is insufficient evidence to prove the effectiveness of masks, yet the organization still recommended their use, reportedly due to political pressure. New York Times (NYT) recently fact-checked claims that seed oils “are ruining our health " and found that they are “not only safe, but [also] heart healthy!”. However, opposing studies are easy to find, implying a more complex truth than claimed by the NYT.

In this essay, we’ll explore the implications of this crisis of knowledge and examine the ways in which the process of knowledge creation has become unhinged. We’ll argue that this crisis is not just a minor issue, but a fundamental threat to our ability to make informed decisions and navigate the world.

Knowledge is a social problem, not an individual problem. Most of what (you think) you know comes through testimony. Most of that is produced by institutions. It’s always selective, always interpreted. There’s no escaping this.

Disagreement is not only about medical interventions or the proper response to pandemics. A YouGov survey conducted in December 2020 found that only 12% of Trump voters believed that Biden’s election was legitimate, despite the absence of any court rulings to the contrary. However, it would be a mistake to assume that Democratic voters are better informed. Another poll from 2018 revealed that a staggering two-thirds of Democratic voters believed, without evidence, that Russia had tampered with the actual vote count on election day 2016, altering the outcome in Trump’s favor.

A January 2021 survey revealed that trust in the mass media had plummeted to a historic low in the United States, with a mere 46% of Americans expressing confidence in the media. This decline in trust has been a long-term trend, accelerated by the rise of the internet, which has increased competition and given consumers more options for accessing information.

This shift has, in turn, led to a profound transformation of the media landscape, a decentralization of unprecedented scale, rivaling that of the printing press era. As a result, it has become increasingly possible for individuals to inhabit separate informational ecosystems, each with its own distinct narrative and understanding of reality.

How can we, as citizens and as a cohesive society, hope to make informed decisions to address the most pressing challenges when expert opinions are so divergent and prone to drastic shifts? Moreover, how can we reconcile the fact that many experts arrive at fundamentally different conclusions, while large segments of the population inhabit separate epistemological spheres, with little common ground or shared understanding?

It is possible that the greatest crisis we face is not one of politics, economics, or environment, but rather a sense-making crisis – a crisis of epistemology, where the foundations of knowledge and truth are increasingly fragmented and uncertain.

Understanding in Crisis: Misaligned Incentives

Show me the incentives and I will show you the outcome.

– Charlie Munger

To better comprehend the sense-making crisis, it may be helpful to begin by examining the underlying incentives that drive the creation and dissemination of knowledge. As the American inventor Charles Kettering astutely observed, “a problem well-stated is a problem half-solved.” In this essay, we will attempt to clearly define the challenges plaguing the knowledge creation process, with the aim of illuminating the root causes of the sense-making crisis. To this end, we will explore several key problems related to knowledge creation, as well as the factors that contribute to friction in this process. The following schematic illustration provides a simplified representation of the knowledge creation pipeline, from conception to public dissemination. Please note that this diagram is not intended to suggest that each intermediate stage is equally problematic; rather, it is a simplified model meant to facilitate discussion.

Figure: The Knowledge Creation Pipeline: A Six-Stage Process

Source: Martin Enlund (2021)

1. Research Question: Cui Bono?

At the inception of the knowledge creation pipeline, a crucial question arises: who decides to investigate a particular research question, and what drives their decision? It is essential to acknowledge that the motivations behind research initiatives can be influenced by self-interest. For instance, how likely is it that the tobacco industry would fund research on the potential harm caused by its products? In the private sector, corporate executives are obligated to prioritize research that promises the greatest profit potential, as this aligns with their fiduciary duty to shareholders. Consequently, the selection of research questions may not always align with the greater good of society. This concern applies to both private and public sectors, although the underlying incentives and structures differ.

Furthermore, certain topics are taboo, while others are not. This, in itself, influences the types of individuals drawn to various fields, and consequently, the questions that are investigated. “If you step on the grass, it will never grow,” as theoretical physicist Avi Loeb aptly puts it.

Case in point: a pharmaceutical company is likely to prioritise research on patentable medicines due to their higher profitability, at the expense of other research (such as natural remedies, where the state does not guarantee monopoly profits). As a result, the sheer volume of research findings will likely support the perceived effectiveness of patentable medicines, even if this is not necessarily the case.

It is essential to note, however, that none of this implies that the scientific method is flawed. Rather, it highlights that researchers, companies, and other organisations can have incentives that lead to biases in the questions being explored.

2. Methodology: As You Ask, So Shall You Receive

In the second step, one should ask oneself if the choice of instrument is the most suitable. Here, “instrument” is meant in a broader sense than the model of a particular microscope. Why, for example, did a person do what he did? If you ask this question to different scientists, you will get different answers. A quantum physicist would refer to changes in probability fields, a chemist to a chemical reaction, a biologist to genetics, a sociologist to socio-economic circumstances, while an economist would say that the person in question wanted to do so. The choice of expert, and more importantly, field, will affect the perspectives that will later be shared with the public.

For instance, a think tank or government agency may hire individuals from a particular field whose underlying assumptions align with the desired conclusion. If sociologists are enlisted, the answer will almost invariably point to socio-economic factors. If biologists are consulted, the answer will be something else entirely, and so on.

3. Result: The Filtered Truth

Not all results are created equal. But should they be? Consider a statistician testing 100 different hypotheses on the same dataset. By chance alone, some will appear statistically significant, a phenomenon Nicholas Taleb has highlighted for over a decade. If only the “statistically significant” results are eventually published, the resulting narrative will be skewed, presenting a distorted or even false picture of the underlying reality.

Regrettably, there is also a risk that experts and researchers may tailor their statements or research to suit interests other than a genuine pursuit of truth. Perhaps it is challenging to arrive at certain conclusions when they contradict the principles that have guided one’s entire career? This, incidentally, is believed to contribute to paradigm shifts rather than gradual development in science. (Paradigm shifts occur when a fundamental change in the underlying assumptions or principles of a scientific discipline leads to a revolutionary transformation in the way that field understands the world.)

It is also possible that experts are motivated by a desire to secure ongoing funding, or are concerned about the opinions of their colleagues. Alternatively, they may be influenced by more practical considerations, such as access to face masks in healthcare settings during a pandemic. Or perhaps they take political considerations into account?

A striking example of this phenomenon can be seen in the field of sociology in the United States. Among American PhD holders in sociology, it is 44 times more common to be a Democrat than a Republican. This disparity is likely to colour Republicans’ perception of the field’s legitimacy, but also risks making the field itself more insular - and potentially even narrow-minded and intolerant.

4. Publication: The Replication Crisis

Once the results are in hand, will they be shared with the scientific community through a published report? The answer, unfortunately, is not always yes. The selective publication of results in scientific journals can create a distorted representation of reality. This phenomenon is closely tied to the replication crisis, where previously accepted research findings cannot be verified through subsequent studies. A notable example from psychology found that only 14 out of 28 research results could be successfully replicated. The number of reports that are subsequently retracted has increased over the past few decades. This has led to questions about the reliability and validity of scientific research.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that, in certain fields, it is relatively easy to get outright nonsense published. This raises concerns about the peer-review process and the ability of journals to detect flawed or fabricated research.

For example, the failure to replicate important and well-known research findings that have been widely accepted for decades has significant implications for the scientific community. How can awareness of this fact do anything but erode trust? Moreover, when journalists tweet about new “breakthroughs,” do they appreciate the nuances and potential flaws of the research they are promoting? Or are they contributing to the hype and perpetuating a culture of sensationalism that can ultimately undermine trust in both the media as well as in science?

5. Media Coverage: The Attention Economy

The incentives driving the media landscape are also fraught with problems, both for media companies reliant on advertising revenue, companies dependent on subscription revenue, as well as with social media firms.

Traditional Media Distorts the Picture

Advertising revenues within the journalism sector have nearly halved since 2008 in Sweden. Meanwhile, in the US, the newspaper industry has lost two-thirds of its jobs over the past 20 years. The media industry is in crisis, with intense economic pressure to generate revenue. Media companies reliant on advertising will do their utmost to attract advertisers and readers – often resorting to clickbait tactics. Those dependent on subscription revenue will strive to entice more subscribers. Perhaps they will gain more subscribers by telling people precisely what they want to hear? This concern has been voiced in the New York Times.

If code scripts machines, media scripts human beings.

“Oh damn” journalism

Swedish journalist Carina Bergfeldt has shed light on a concerning trend in the media industry. A evening newspaper has employed the concept of “åfanismen”, a term used to describe the goal of crafting articles that elicit a strong emotional response from readers, making them exclaim “oh damn”. While this approach may drive engagement and boost circulation, it comes at a cost.

By prioritizing sensationalist “oh damn” news, the newspaper presents a distorted picture of reality. The focus on extraordinary and attention-grabbing events creates a skewed perception of what is normal and common. As the old adage goes, “man bites dog” is more newsworthy than “dog bites man”. However, if only the former type of news is published, readers will be led to believe that men biting dogs is a more frequent occurrence than it actually is.

Globalization has also played a significant role in the distorted reporting of reality. With the advent of digital media, news from around the world is now at our fingertips. While this increased access to information has many benefits, it also creates a unique problem. Today, you can read about the man who bit the dog, even if it happened in New Zealand. This globalization of news can create a skewed perception of reality, making it seem like such incidents are more common and widespread than they actually are.

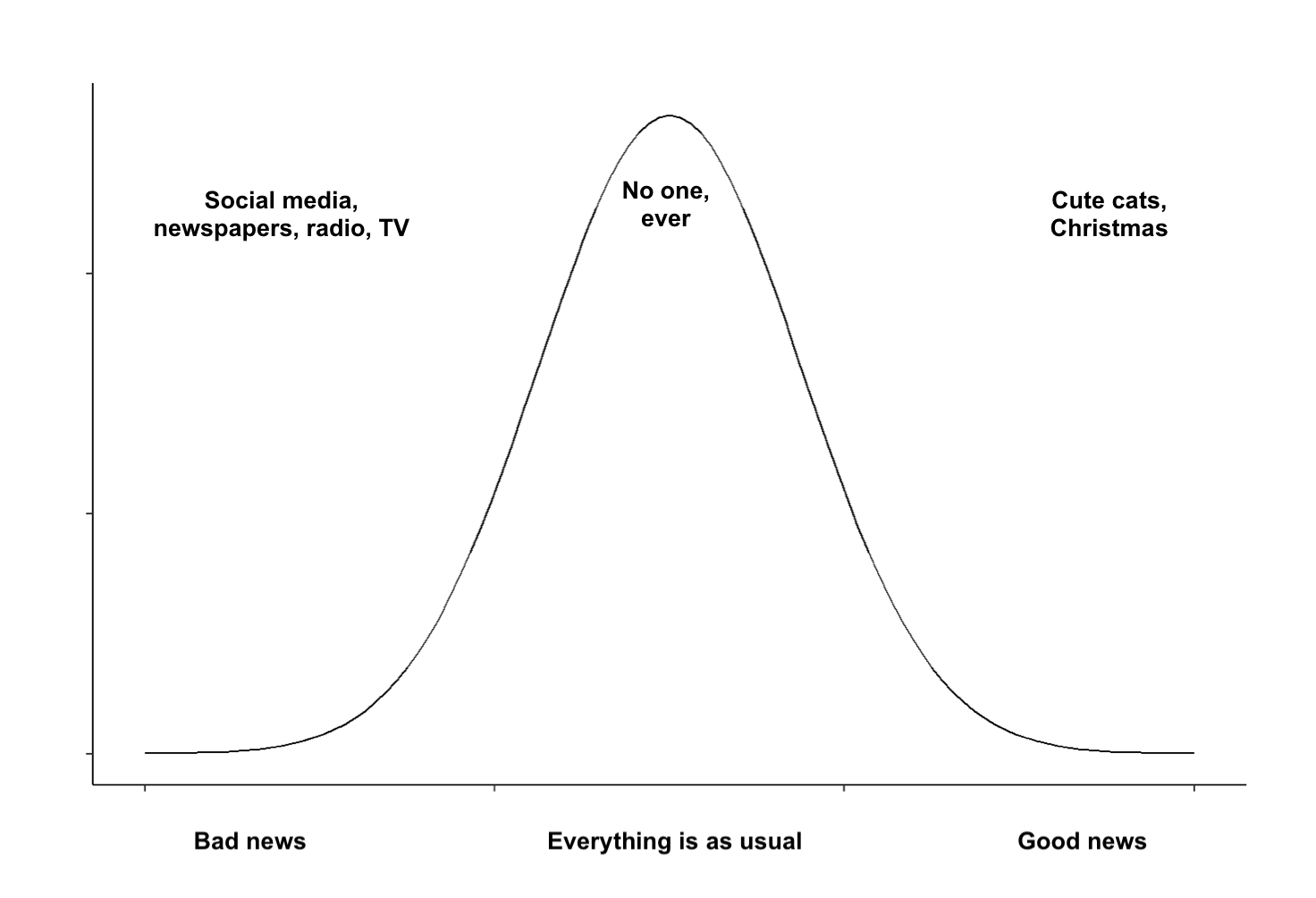

Figure: Probabilistic Reporting

Source: @PolemicTMM

The concentration of journalists in urban areas also risks presenting a narrow picture of what is reported. For instance, there are 17 times more journalists per capita on the island of Södermalm in Stockholm, Sweden’s capital, than in the Nordmaling municipality. These two areas have distinctly different voting patterns. How can this not contribute to a distorted picture of what issues are considered relevant to cover, and how? People are, after all, still people.

Case in point: the market-economic logic that drives privately owned media companies creates inherent incentives to present a distorted picture of reality. This is true regardless of whether they operate under an advertising model or a subscription model. The pursuit of profit can lead to sensationalism, selective reporting, or a lack of nuance in the presentation of complex issues. Similar problems exist with state-funded media companies and non-profits, where the influence of government or special interest groups can also lead to biased reporting. Furthermore, globalisation and centralisation trends have exacerbated the situation, creating a media landscape where a small number of powerful companies and organisations wield significant influence over the flow of information.. This concentration of power can stifle diverse perspectives and limit the availability of accurate, unbiased information.

Social Media may be Even More Problematic

Contrary to popular perception, Facebook is not the product – you are. Social media companies generate revenue primarily through advertising, which creates a perverse incentive to keep you engaged for as long as possible. This can lead to a phenomenon known as “addiction by design,” where platforms are engineered to activate the brain’s reward system, releasing feel-good chemicals such as dopamine. For instance, Facebook’s first “monetization” chief, Tim Kendall, once testified that the company drew inspiration from the big tobacco companies and deliberately designed their platform to be “addictive from the start”. Moreover, more than ten years ago, Facebook deliberately made about 155,000 people sad, just to see if it could. Such admissions raises disturbing questions about the ethics of social media companies and their impact on our mental and emotional well-being.

What worries me most is that people pay attention to how many likes they have on Twitter

– Avi Loeb

Social media companies have a profound impact on our perception of reality, and it’s not always for the better. Their algorithms are designed to maximize screen time, serving us content that elicits strong emotional responses or confirms our existing biases. This can lead to a distorted view of the world, where sensationalism and misinformation reign supreme. Twitter’s algorithms are a prime example. Sensationalist – and often false – news spreads rapidly, while debunkings and retractions are relegated to the fringes of the conversation. This creates a breeding ground for misinformation and disinformation.

The market-economic logic of social media companies is also troubling. Their primary goal is to keep you engaged in an endless cycle of consumption, known as “doomscrolling”. This enables them to sell ads more effectively. They also sell information about you to third parties. The consequences of such business models are far-reaching, contributing to the erosion of trust in institutions, the spread of misinformation, and the manipulation of public opinion.

6. Public Perception: A Warped View of Reality

As humans, we also employ a range of mental shortcuts that often lead us astray, known as the availability heuristic. Psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have devoted significant portions of their careers to this and related phenomena. Interestingly, even they have been forced to revise their book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” due to their excessive trust in certain studies.

cognitive 👏 bias 👏 is 👏 when 👏 people 👏 believe 👏 things 👏 i 👏 think 👏 are 👏 wrong

A striking example of the media’s influence on our perceptions can be seen in the way it reports on police brutality. Exposure to media coverage of excessive police force can create a distorted perception of its prevalence, leading people to believe it is much more common than it actually is. Furthermore, this effect is more pronounced among liberals than conservatives, suggesting that preconceived notions and confirmation bias play a significant role in shaping our perceptions.

Another illustrative example is the public’s perception of homosexuality in the US. Despite surveys indicating that the actual proportion of homosexuals in the population is less than 5%, Americans estimate that a staggering 24% of the population is homosexual. This significant discrepancy raises important questions about the role of media in shaping our perceptions. Is it not a reasonable explanation that the public is being provided with a distorted view by the media, one that contributes to a skewed understanding of reality?

Readers may also, if they wish, ponder the bombing of Yugoslavia, the invasion of Iraq, or why not the Gulf of Tonkin incident. How were these military interventions justified in large parts of the American media at the time? And what do we know about these affairs today?

Conclusion: What a Tangled Web We Weave

In conclusion, we hope to have demonstrated that the knowledge creation pipeline is beset by a multitude of problems, driven by skewed incentives that can render claims made by researchers, journalists, media companies, and others unreliable. These distortions can have far-reaching consequences, ultimately affecting the accuracy and trustworthiness of the information that reaches the public.

The problems are indeed enormous, and this is already the case before a wide-spread advent of “deep fakes”, which promise to further complicate the landscape. Advanced algorithms can already create convincing fake videos of public figures, such as Tom Cruise, and soon it will be impossible for most people to determine which audio or video clips are genuine or not.

While some of these problems are being addressed, particularly in the scientific community’s efforts to address the replication crisis, progress is slow and only addresses a small part of the problem.

The question becomes, in light of the above frictions, what one can do if one still has the ambition to understand the nature of things - or at least the ambition to try to avoid being swept up in the worst tendencies.

Strategies for Navigating the Sense-Making Crisis

It is unlikely that individuals can completely avoid misconceptions about understanding. However, by adopting a critical and nuanced approach, one can take steps to mitigate these distortions. A few modest recommendations can be offered:

- Be aware of the perverse incentives that drive traditional and social media, which can actively work against a balanced understanding of reality. The fact that something becomes a trend on social media be utterly meaningless.

- Approach information with a healthy dose of skepticism, particularly when it elicits strong emotions. When you find yourself becoming upset or outraged, pause and reflect on the potential motivations behind the message. Ask yourself: did someone intentionally try to manipulate my emotions, and if so, how did they achieve this?

- Another useful rule of thumb can be to primarily trust only news that is reported consistently by e.g. both CNN and Fox News. If either of these two outlets disputes the accuracy of a story, it’s likely time to exercise skepticism and caution.

- Another valuable heuristic is to seek out information sources that do not seem to have a vested interest in the outcome of a particular narrative.

Another innovative approach is to utilize platforms like ground.news, which tracks news stories from various media outlets across the left-right spectrum, providing a unique perspective on the biases that can emerge. It may also be a good idea to venture beyond the confines of centralized platforms, which often employ opaque algorithms to curate content and shape your online experience. By exploring decentralized networks and alternative sources of information, you can regain control over the content you consume and mitigate the influence of hidden biases and agendas.

These ideas will be explored in greater depth in future articles. In the meantime, we invite you to share your thoughts and opinions on the matters discussed here. Your feedback is invaluable, even if your views differ from our own. If you’d like to get in touch, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us through our contact page.

Cover image: The capsizing of Seawise University, formerly RMS Queen Elizabeth. Source: Wikimedia Commons